Scott Wing

A Pore Story

High levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere cause temperatures to rise globally. But during the Eocene, temperature differences between the poles and the tropics were smaller than they are today. This pattern suggests that factors in addition to carbon dioxide in the atmosphere might have been at work. Paleoclimatologists (scientists who study ancient climate) like the Smithsonian’s Scott Wing want to know how much carbon dioxide was in the atmosphere during the Eocene.

How do they find out?

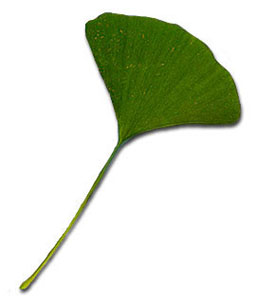

Ginkgo trees that grew during the Eocene Epoch were almost identical to those that grow today. A team of paleoclimatologists, including Dr. Scott Wing from the National Museum of Natural History, has used Ginkgo fossils to estimate the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

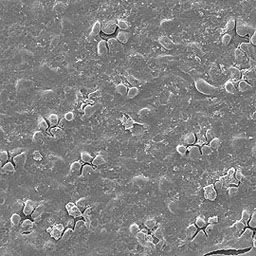

Tiny pores, or stomata, on Ginkgo leaves act like little mouths to let in carbon dioxide used in photosynthesis. As the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases, leaves can take in the same amount of carbon dioxide with fewer pores. Careful counting under a microscope shows that the density of pores on fossil Ginkgo leaves is about the same as the density of pores on leaves of living Ginkgo trees. This finding suggests that the amount of carbon dioxide in the Eocene atmosphere was not very different from present, and some factor other than atmospheric carbon dioxide was responsible for warm Eocene climates.

Some paleoclimatologists think that warmth at the poles was the result of higher atmospheric levels of water vapor or methane, which, like carbon dioxide, are greenhouse gases. Methane may have created clouds of ice crystals that held in heat over the poles like a planetary ski cap.